Bach, Cantata No. 20. T. Herbert Dimmock discusses the artistry and word painting in Bach’s Cantata number 20, BWV 20. BDP #261. www.bachinbaltimore.org.

In June, 1724 Bach was living in Leipzig, where he remained

until his in 1750. He had moved to Leipzig at the beginning of 1723 and settled

into the job as cantor (or music director) at the Thomas Kirche, one of the

biggest jobs in all of Germany. In 1724, one year into his new, prestigious job

he wrote a cantata entitled: “O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort” (“O eternity, you word of thunder”).

In an opinion shared by all who know it, this is one of the

most fabulous pieces of music to have been written at that time. Bach imbues

the piece with wonderful symbolism, imaginative examples of word painting, and

innovative, creative ways of bringing out and underscoring liturgical points

not explicitly contained within the text. It’s the achievement of a world-class

genius. Let’s take a moment to look at a few of the many highlights within the

cantata.

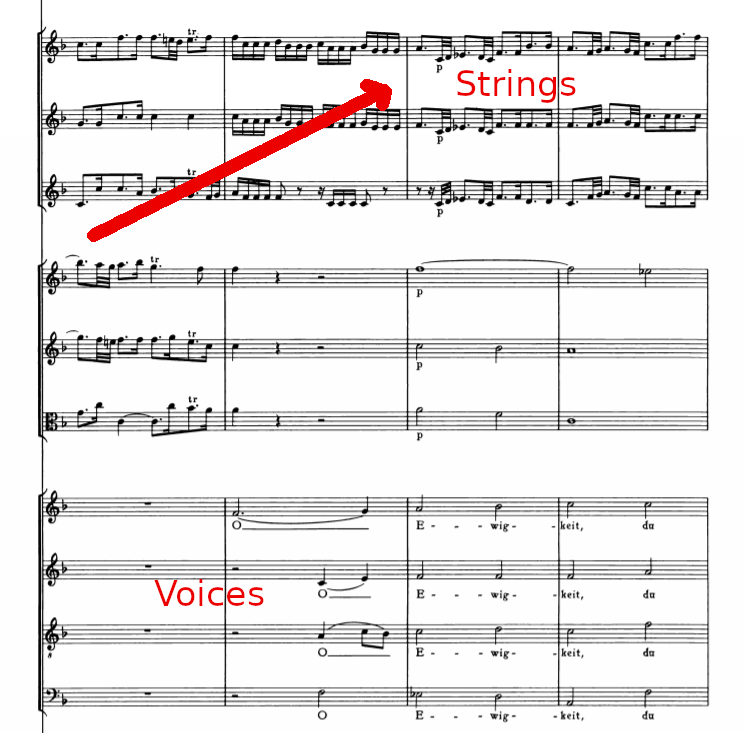

First of all, the piece starts with a highly rhythmic pattern dubbed the “French Overture” style. The French Overture style was one of Bach’s absolute favorites to which he turned when he wanted to alert his audience that the music they were about to hear referenced royalty. Of course, for Bach ‘royalty’ did not refer to the king of Germany, but rather the King of the universe, God. Thus Cantata 20 begins with the violins in the orchestra playing this: (music).

The repeating rhythmic figure you heard of a long note followed by a very short

note has been given the name of the French Overture style. Bach’s music

therefore informs us that the subject matter he is about to set to music is

focused on God. By virtue of using the

French Overture style, Bach makes the musical point that the “word” come from

God and therefore it is both eternal and righteous. It’s well worth reminding

ourselves that for Lutherans, like Bach, the “word” referred to the Bible. In

contrast to the Roman Catholics and their emphasis on the hierarchical church,

for Lutherans the Bible was given the place of highest honor.

A notable feature of Cantata 20 is its overall construction

as a “Chorale Cantata”. That is to say, Bach uses a chorale melody (what today we

would label as a hymn tune), as the basis of the entire extended piece. In the

opening chorus, while the orchestra is playing in French Overture style, the

sopranos sing this hymn tune melody which appears at both the beginning and end

of the cantata. That chorale melody sounds like this (music).When it is sung at

the end of the cantata, it is presented in four-part harmony with full choir

(music)… quite similar to what one hears when a hymn is sung in church these

days. However, at the beginning of this cantata while the orchestra is playing

in the French Overture style, the sopranos sing the tune (music with

conducting) supported by the orchestra playing a French Overture style accompaniment.

(music). As noted a moment ago, Bach’s point is that the eternal “word” comes from

God.

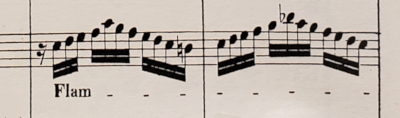

As we move through the cantata, Bach adds many interesting details. High on the list is a compositional device that Bach employs quite often entitled: “word painting.” Word painting is easily described. It is music that is composed in such a way as sound like what the words set to it actually mean. In the first aria, written for the tenor, when Bach composes music for the word “flame,” Bach paints a visual picture of a flame in his score. Flames crackle, flickering up and down.

Our soloist sings a long series of notes that imitate a

flame, flittering up and down. The flame, like the music, dances and crackles

away. Immediately preceding the tenor’s singing of the word “flame” the cellos

and basses in the orchestra play a series of two note laments – foreshadowing

the pain and suffering that one would have to endure if thrown into the eternal

flames of hell. In fact, the focus of

the entire tenor aria is to explore what damnation would mean. The text is: “If

one does not live a just life, he is banned in eternity.” Once again, Bach seizes

this opportunity to enhance the meanings of the text through the compositional

device of word painting. “Eternal” (in German, “Ewigkeit”) offers an easy

solution. Bach simply writes a very long

note – a literal example of ‘eternal.’ While the tenor is singing “Ewigkeit”

the orchestra returns to the sad, lamenting pairs of notes that we noted a

moment ago with the eternal flames of hell. This time however, all the upper

strings play the pairs of notes in parallel chords. Harmonically, that hovering series of

parallel chords depicts the angels. They hover over the damned, weeping and

lamenting the terrible fate of the soul in hell. (music)

Bach’s music was intended to be a wake-up for his

congregation. Bach’s fervently believed that everyone one should live righteously

– or pay the ultimate price. That’s why Bach saved the use of the trumpet for

the bass aria which opens the second half of

the cantata. What better instrument to use than the trumpet, the royal

instrument, to call folks to wake from their slumber? It should come as no

surprise that Bach again uses the French Overture rhythm again at this very

spot (music). The trumpet fanfare which jumps up and down the scale, urges us all

to “wake up.” The bass soloist makes certain that we all get the point, he sings

those very words after the trumpets exhilarating introduction (music). “Wake

up, wake up.” “Wacht auf, wacht auf.” (music). Up and up he goes. Bach has the

trumpet and strings join in with dramatic fanfares of their own. (music) All

then unite into a gorgeous, compelling musical whole. The clear, single focus

of this entire, exhilarating aria is to compel us all to “wake up.”

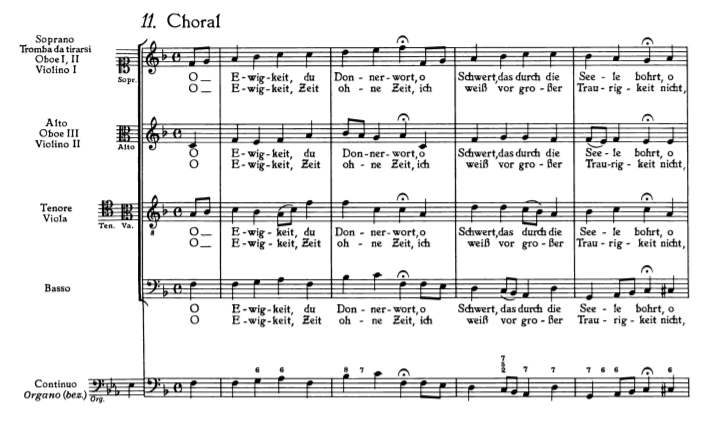

As mentioned earlier, this cantata is a chorale cantata. Thus, we conclude the entire piece with the same the melody that we heard in the beginning. The choir again references the “eternal word” concluding with the prayer that “in the end” (at our death) we will be taken to “God’s eternal tent” (heaven). The closing chorale is sung in four-part harmony in a traditional way by the choir accompanied by the orchestra. (music)

In Cantata 20 Bach has built a magical, multi-movement work focusing on his belief that one journeys on the path to heaven by adherence to the “word.” Throughout the cantata, Bach masterfully brings out deeper meanings of the text with his imaginative use of word painting. In fact, many of the points that Bach wishes to convey are purely musical. That is to say, they are not made by the text but rather in the music associated with the texts. Bach was a master of that technique. In fact, Bach was so adept at it that he was given the moniker of “the fifth evangelist” in his lifetime. His music so powerfully tells and explores the stories which he set to music that people in his community likened it hearing a great, compelling preacher. Regardless of your personal beliefs, I know that you can agree with me: it sure is beautiful music.

<graphic examples from imslp.org>

<music: J. S. Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 1>