Handel, Messiah, Part 1. T. Herbert Dimmock discusses this iconic

work by G. F. Handel. He provides an introduction to the work and discusses

French Overture style and word painting. BDP #265. http://bachinbaltimore.org/

George Frederick Handel was born just fifty miles away from

Bach in the same year, 1685. When we give the dates for the end of the Baroque

period we use the date 1750. 1750 was the year that Bach died. Although Handel

was not to die until nine years later, 1759, Handel was ill the last years of

his life and wrote very little music. So, choosing 1750 becomes a good choice.

Handel moved to England later in his life and began to write oratorios.

This was an interesting thing because oratorios were not common until Handel

began to write them. He wrote them because the Archbishop of London decreed

that during the time of Lent people were not allowed to have certain kinds of

music. Oratorios, being based on Biblical texts, and not being staged, were

different than opera. They weren’t staged but they still had a chorus,

orchestra, and soloists. So, Handel began to write English language oratorios

late in his life, when he was at the height of his powers.

In 1741, he wrote Messiah. I visited the Handel house in

London and sat in the room that Handel wrote that piece. It is a small room

about 10 x 12. There are no windows. Handel famously locked himself in that

room and didn’t come out until the Messiah was finished in a period of just a

matter of days. We know that Handel was probably manic. On one level we are grateful

that we did not have modern medicine in those days. If we did, he probably would

be taking something for his illness, and perhaps we would not have what is

considered quite arguably the greatest choral work ever written.

What makes it so great? Well, Handel has put together these

musical ideas that go throughout the entire work and in a wonderful way tie it

together. In addition, each of the fifty movements of the piece stand on their

own magnificently well. Because they stand by themselves well, sometimes people

don’t realize these common, wonderful threads that pull this together. So,

let’s look at some of those threads. For me, when I perform Messiah, when I

lead a concert, it is one of the things that I have in mind, to perform it in a

way that will bring that out.

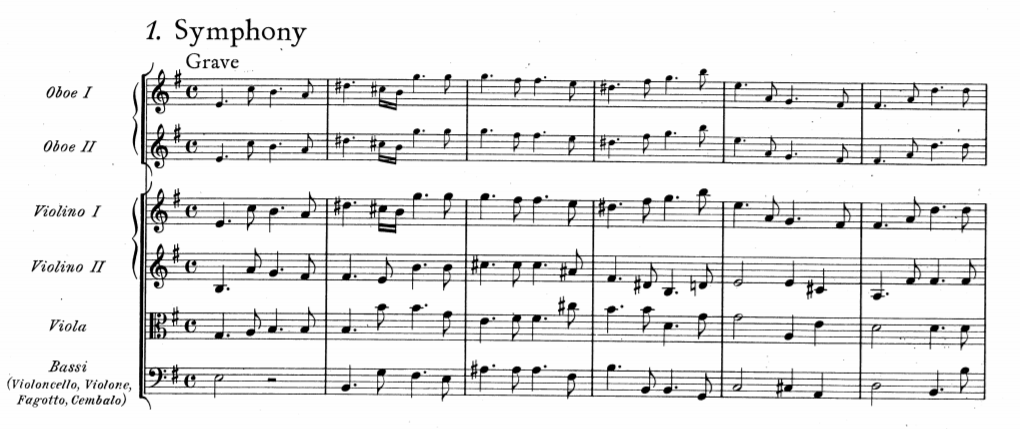

The piece starts with just the orchestra playing in this style. (music) That style, where the first note is quite long followed by a very short note (Ba---Ba Ba---Ba Ba----) is called the French Overture style.

This

is the style that was associated with King Louis of France and therefore was

royalty. Bach and Handel start many of their pieces that have to do with God

using that style. The style say that this has to do with royalty. In Handel’s

case in the Messiah, he is saying that the Messiah was a royal messiah. What

kind of royal messiah? A godly messiah.

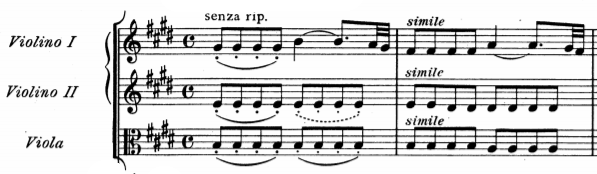

Right after the opening overture, we have the first piece for tenor soloist. It sounds like this. (music) This figure… (music) followed by this one… (music) and this one (music).

It

is the second major figure delivered to us in the Messiah. What is that, these

repeated notes? (music) These repeating notes is a comforting figure. In fact,

the text is “Comfort ye.” It is a figure like a loving parent, comforting by

tapping gently on the back of a baby, perhaps, that needs to be settled down to

go to sleep. This idea of comfort, Handel puts it into the music. What is

interesting to me is—you may not realize that until it is pointed out to

you—that once it is pointed out, you can’t miss it. Once you realize it is

there you know what a lovely thing it is in the music. (music) That is called a

recitative, “Comfort ye, my people.”

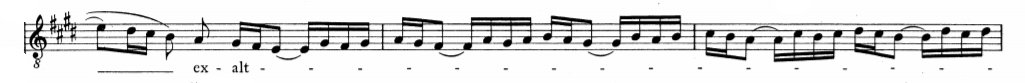

That is then followed by the first aria. Beginning with this first aria we have one of the many wonderful, fascinating examples of word painting. Handel loved to use word painting in his music. Word painting is when the music sounds exactly like the word means. He couples that which what is called the “Doctrine of Affections.” Today if you see a friend you might say, “How are you feeling?” or “What is your mood?” In those earlier times, in the 17th and 18th centuries, people talked about somebody’s affect. Baroque composers believed that certain musical figures could make you change your affect. Handel writes in this opening piece, “shall be exalted.” (music). What is it about that? There is an exuberance. How about the fact that it goes…(music) it keeps jumping forward to the next figure and goes up the scale. There is an exuberant quality to that, which brings out the meaning in the word “exalted.”

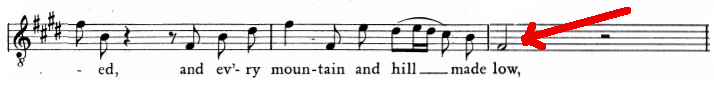

Then there are these obvious word painting things where the music just sounds like this. So, in “every mountain and hill made low.” (music) It drops down for the word “low.” So and so forth. In the music you have all of these ideas where the music lovingly and effectively matches with what the text is.

<music: J. S. Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 1>