Bach, Christmas Oratorio; Parts 1 and

Parts 5, BWV 248. T.

Herbert Dimmock introduces the Christmas

Oratorio with comments on the opening and then discussion of

several

examples from Part 5. BDP #268. http://bachinbaltimore.org/

Johann Sebastian Bach’s

lifetime work was actually the

writing of cantatas. We know his wonderful organ pieces. We certainly

know his

instrumental music, even though there is not nearly as much of it. Bach

in his

lifetime probably wrote 300 or more cantatas, each of which are about

twenty

minutes long. Bach lived from 1685 to 1750. At the absolute height of

his

powers, when he was in Leipzig in 1734, he wrote six cantatas that

stick

together into a whole, which is called the Christmas

Oratorio.

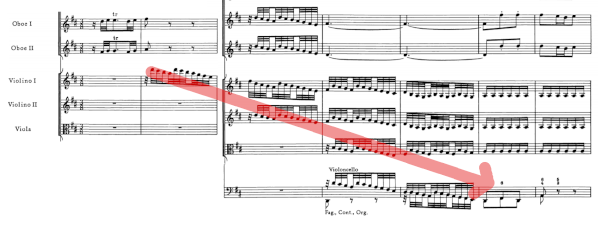

The Christmas Oratorio is a wonderful piece. I can’t tell you enough how I love the way it starts. How many pieces start with just the tympani playing by itself? Well, the Christmas Oratorio does. It is a signal motif that says, “Wake up!” as the timpani (music) has a little fanfare motive. It is interesting to me that the orchestra wakes up one at a time. First the flutes, they wake up. (music). Then the tympani plays. (music) Then the oboes wake up. (music) Then the tympani comes back. (music) Now the strings come in—this is so magnificent. They start at the highest note possible and it comes down, rip roaring through the strings, passed over to the violas, then the cellos, and then the basses. Of course, the double bass plays down the extra octave. There is this spectacular five-octave scale that takes place in the course of four measures. In a fast tempo it is a picture of God crashing down from heaven above to earth below.

That is the first beginning of the Christmas Oratorio. The Christmas

Oratorio is six cantatas written for Christmas. Christmas day

1, Christmas

day 2, Christmas day 3, Christmas the Feast of the Naming of Jesus also

called

the Feast of the Circumcision, the first Sunday in the New Year, and

the Feast

of the Epiphany--six cantatas.

On the first Sunday of the New Year,

we get Cantata 5. First

of all, let’s talk about how the piece is put together. In

this particular

Cantata Bach features the oboe d’amore. The oboe

d’amore is one of Bach’s

favorite instruments. It is not an instrument that we use much in the

modern

orchestra today. If you think of the regular oboe as this big, and you

think of

the English horn as this big, then the oboe d’amore is in the

middle. It has a

bell-shape bottom. It has a beautiful dark sound that Bach so loved.

The text is “Ehre sei dir, Gott, gesungen” “Honor be sung to Thee, oh Lord.” This opening melody is first given by the oboes. They play it in a way that talks about how we should sing it to the Lord. The Lord, of course, is in heaven above. So, the oboe d’amore… (music) the oboe d’amore directs our attention to where praise should be sung. It starts way down here (low note) and ends way up here (high note). Bach is directing through the instruments; the instruments are presenting a commentary on where the praises should be sung. When the singers come in they sing a melody that goes up. When they get to a word “Lob,” which is German for praise, there is wonderful exuberant quality to the word “Lob.” It goes upward. It goes up in a way that is eager to do so.

You would think…(counting and singing) but Bach goes

… (counting,

singing, and playing). He leaps in early because there is an eagerness

in

giving the praise. The word Lob goes up (music). The second word is

“Dank” and

again in the word “Dank” that comes with the word

praise we have lightness, a

quality of thanks that goes upward.

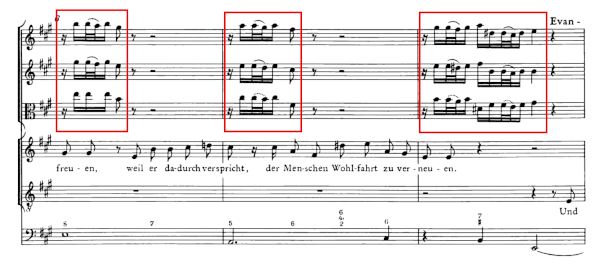

Why do we call this the Christmas

Oratorio instead of just six cantatas? This is one reason

alone and one

reason only. It is because the tenor soloist is given a name. He is

called an

“Evangelist.” The tenor soloist sings the text of

the Bible that tells the

story. For that reason, to differentiate it from the other cantatas

where all

of the singers are just called, “soprano, alto, tenor, or

bass” we call this an

oratorio.

Bach was a deeply religious person. He was what was called a pietistic Lutheran, a “heart on your sleeve,” a profoundly religious person. In the Christmas story at this point King Herod is saying that all of the newborn babies have to be killed. This is a very awful and sad thing. At this point of the story we have this (music). Why do we have sorrow here, why are we so upset? (music) This is somebody shaking with fear, if you will.

Well, the Tenor passage—this

is pietistic Lutheranism in

Bach’s time, in a “nutshell.” We had to

have the sacrifice of Jesus to have salvation,

to have Easter Sunday. We had to have the negative parts of the story

for the

ultimate good outcome. So, at this moment in the story (music) why do

we have

sorry here? The singer says “there is much to rejoice for,

since God’s own plan

will gain the sinful world’s salvation. Then he transforms

those figures to

(music). From the minor to the major, from the shaking sadness to same

kind of

rhythmic figures, but suddenly they are happy figures. In

Bach’s mind, this

terrible part of the story actually leasds to something good.

This is a wonderful cantata within the

Christmas Oratorio, as

they all are. I hope that you will have a chance to come and listen to

it. It

is well worth it!

(music: J. S. Bach, Brandenburg

Concerto No. 1)